Indigenous Maya Labor in a Site of World Heritage

by Sofia Vicente-Vidal, Tinker Grantee; Master’s candidate, Department of Anthropology

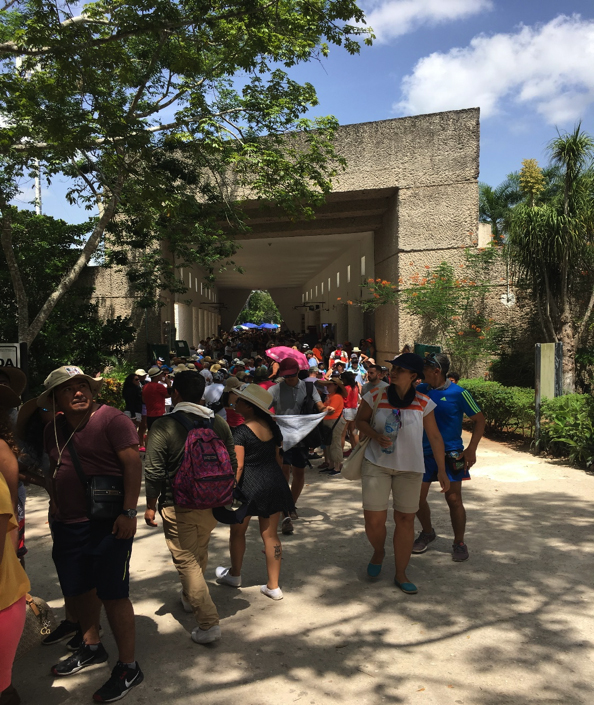

With the support of the Tinker Field Research Grant, I was able to return to Pisté, Yucatán, Mexico to expand on initial research exploring the ways in which the tourist economy has created or increased social and economic class divisions among the Maya men and women that work in and around the archaeological zone of Chichén Itzá. Additionally, my research explores how Maya identity is conceptualized by each group of workers to find how cross-class conceptualizations of “Mayaness” are similar or different, and how the tourist economy and nationalist discourses influence those ideas of indigenous identity.

While initially wondering about workers within the zone (government employees, artisan and food vendors, tour guides), I expanded my scope of inquiry to include workers who regularly traveled to Pisté from other towns within the municipality and local Pistéños that work selling handcrafts in the town center. Official government workers of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) arguably benefit the most from the site; their work as custodians of the monuments is unionized, includes a sizable salary and benefits, and they enjoy freer access to the site.

Other Pistéños make a living working several jobs in the tourist industry both in and out of the site grounds. By conducting life-history interviews, I was able to ask Pistéños about their experiences growing up in the town, how it has changed around increased bureaucratic institutions surrounding Chichén Itzá, changes in the economy and viable modes of livelihood, and differential access to the site itself.

Don Agustín is a recently credentialed tour guide during the day and works as a troubadour entertaining hotel guests in the evening. Recounting his life history in Pisté, one is able to imagine the ways in which the social landscape has been reconfigured by the construction of Chichén Itzá as a site of UNESCO World Heritage as well as one of the “New 7 Wonders” of the world.

When asked about changing access to the site, Don Agustín related that, before receiving his official tour guide credential, he made a bit of side money as an unofficial tour guide, taking groups inside the zone and recounting histories of the ballcourt, the Sacred Cenote, and the Temple of the Warriors. In the middle of one of his tours, he was interrupted by a government custodian:

“Since I was very young, I walked into Chichén, I climbed, I went up and down. I know this edifice from its foot to the top. So, who else can inform people better than someone who knows it? I entered with some friends that were visiting Mexico. And of course, the person that officially represents tourism came over to tell me that I cannot give out information. “You don’t have a credential, you don’t have permission, you don’t have anything. You can’t give people explanations.” One of the people in my group, a lawyer, interrupted the official to tell him that I was the only, and the best, to tell the story of my own buildings and my own land.”

Don Agustín eventually saved to enroll in and complete the tour guide training course and receive his credential. His story, however, indicates how economic structures around industries within and around the zone have increasingly reduced locals’ access to the site and regulated work within the zone.

In preparation for my master’s paper, I’ll elaborate on issues of access, spatial reconfiguration, differential modes of livelihood at the cross-sections of class and gender, the way younger generations of Pistéños imagine their futures, and the larger political economy of Tinúm. Although Tinúm Municipality is the home of a world-renowned heritage site, the benefits of its global notoriety hardly reach the Maya people of the other towns of the municipality.

—Sofia Vicente-Vidal earned a BA in anthropology from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 2014. Her research focuses on nationalist discourse of Maya identity in Mexico in connection with local Maya communities home to tourist economies.