Immigration and Gendered Violence

Immigration and Gendered Violence

by Kathryn Miller

Just as in the broader U.S. population, immigrant women are subject to gendered violence in their own homes. Unlike in the general population, however, these women’s experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) are layered with the complex vulnerabilities of immigration status. Many come to this country on conditional visas that require them to stay in their relationships in order to maintain their authorization status. This becomes a particularly troubling characteristic of conditional visas when the relationship is abusive. I was in New York City to talk to people—to learn from immigration lawyers, and non-profit workers about the relationship between government policies (or the absence thereof) and the plague of IPV committed against immigrant women in this country. These are the people on the front lines, facilitating interactions between immigrant women seeking to sever the conditional visa status that tethers them to their abusers, and the government institutions tasked with delegating the very limited immigration relief.

The existing relief visas were established by the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). One, commonly called the U visa, has an annual cap of just 10,000. The first U visas were issued in 2009, and the cap has been easily reached every year since 2010. According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the backlog of U visa applicants has reached almost 40,000. U visas in particular were created to facilitate police investigations and the prosecutions of those committing these crimes—women are granted the visa so that they are free to testify against their abusers without fear of retaliatory deportation or detention.

Alex’s office is in an unassuming building in lower Manhattan, just blocks from Wall Street and the heart of the financial district. Her desk looks like mine, piled high with papers and books. She is an immigration lawyer for a prominent nonprofit organization. Her job is to help women get independent visas so that they can escape their violent relationships.

Despite the considerable need, Congress refused to increase the number of U visas when it last reauthorized VAWA. Alex asked, rhetorically, “[i]f the whole point of the [U] visa is to help law enforcement, why would you limit the number?” Her question suggests an answer having less to do with the policy’s stated logic, and more to do with the narrative surrounding the immigrant women it purports to help.

The reauthorization of VAWA stalled in part because of Republican fears that to increase the number of U visas would open the door to immigration fraud. The focus of the debate shifted away from stopping gendered violence, and toward the trustworthiness of those survivors courageous enough to seek immigration relief. Alex lamented this: “It’s frustrating for me…There are these women who are breaking free of abusive relationships, getting their children into safer situations,…reporting family members for terrible things that they’ve done, and it just bothers me that they get brushed with this whole illegal alien paintbrush.” With a sigh of frustration, she added: “This person put a rapist in jail. That’s an amazing thing that they’ve done, and it’s good for society…The fact that the VAWA reauthorization process was so contentious was really upsetting. I mean, who’s against this?”

For Alex, the effects of these debates and the resulting policy limits are clear—many women who ought to have access to immigration relief so that they can excise themselves from violent relationships are instead forced to stay. This research seeks to explain the political and institutional dimensions of why and how these women are forced to stay. Through a better understanding of the role of government policies in this context, we can move closer to ending this form of gendered violence.

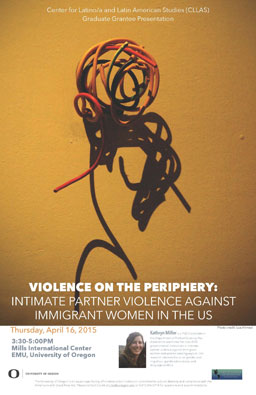

—Kathryn Miller is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science. Her dissertation, “Violence on the Periphery: Gender, Migration, and Gendered Violence against Immigrant Women in the U.S. Context,” examines the role of U.S. governmental institutions in intimate partner violence against immigrant women and women seeking asylum. Her research interests focus on gender and migration, gendered violence, and language politics.