Graduate Student Project

With the help of a CLLAS graduate student research grant, I spent the summer of 2013 in Colombia. I explored gendered patterns of labor in the cut flower industry and the impact of the 2012 U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement on workers. Colombia’s cut flower industry, which resembles factory work, follows a global trend: feminization of labor in which international capital relies on undervalued labor of women, which is crucial to capital accumulation.

With the help of a CLLAS graduate student research grant, I spent the summer of 2013 in Colombia. I explored gendered patterns of labor in the cut flower industry and the impact of the 2012 U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement on workers. Colombia’s cut flower industry, which resembles factory work, follows a global trend: feminization of labor in which international capital relies on undervalued labor of women, which is crucial to capital accumulation.

Colombia is the world’s second largest exporter of cut flowers and women make up 70 percent of the workforce. Women workers face gender discrimination, work long hours, and endure debilitating occupational illnesses and injuries. However, many workers fear speaking out about labor violations because of serious repression of labor organizing and unions. In fact, Colombia has the highest murder rate of trade unionists in the world, and the rate of impunity is staggering.

In April 2012, in spite of concerns about Colombia’s poor record on labor violations and impunity, Obama announced the implementation of the U.S.–Colombia Free Trade Agreement (FTA). One year prior to the implementation, in April 2011, the Labor Action Plan (LAP) was created to address Colombia’s poor record of labor violations in order to pave the way for the FTA. The flower sector was one of the five prioritized sectors in the LAP.

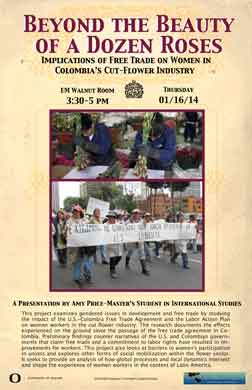

During my fieldwork, I interviewed women cut flower workers who had either previously worked in the flower industry or were still employed. I also talked with grass-roots labor organizers, NGO workers, and staff working at the national level on labor issues. I had access to archives through my internship with an NGO that has worked for 30 years on gender and labor rights in the cut flower industry. While I was in Colombia workers across sectors mobilized in a nationwide protest against free trade and labor exploitation. I observed and participated in several marches in which hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets, insisting on economic justice and an end to impunity.

Union participation and labor organizing in the flower sector has suffered in the last several years. Additionally, the experience on the ground is that the LAP has done little to improve conditions for workers. Many interviewees reported that conditions are worse than before the FTA. Free trade has placed additional pressure on plantation owners to compete in the globalized market, and in turn, they squeeze more work out of the workers. Women workers suffer from chronic job-related illnesses that affect their ability to maintain their households, and they often go without healthcare because they cannot afford the increasing costs of privatized healthcare. They are frequently subject to termination without just cause, and those with health issues are not rehired. Many of the women are heads-of-household struggling to support themselves and their children on minimum wage, living in a state of chronic poverty.

For women workers, the long hours combined with their second shift (household work) constrain their ability to participate in union activities. Lack of time combined with a fear of being “blacklisted” for union participation means that most women only seek out union support when they are desperate. In response to the low participation in unions and continued exploitation of women cut flower workers, there are grassroots efforts working to transform the ways in which organizing can reach and engage workers and plantation owners more effectively. These efforts have made some improvements on a company-by-company basis and have potential to do so across the sector. However, transformative social and economic change must come from development and trade policy that addresses underlying causes of gender inequality and poverty.

This research was also generously funded by the Department of International Studies Thurber and Slape Awards.

—Amy Price is a graduate student in the Department of International Studies. Her background in sociology informs her research interests, which include gender, development, inequality, immigration, and labor. Prior to grad school, she worked for 13 years in a nonprofit organization for people with severe and persistent mental illness. She has volunteered for immigrant and refugee organizations and participated in several activist movements toward sustainable economies and social justice.